Digging deeper into Dungeness

In the past, this time of year would be when many Monterey Bay locals start planning their menus for Thanksgiving. Dungeness crab—a West Coast seafood delicacy—often tops the list.

Unfortunately, climate change and other factors have greatly complicated what was once a predictable and cherished part of a holiday feast.

Whether it’s domoic acid caused by warmer water, or the potential risk of entanglements with migrating whales, or tricky negotiations between fishermen and their buyers—the holiday season no longer guarantees fresh crab.

The crab season, scheduled to start Nov. 15, has already been pushed back to Dec. 1.

While this may be disappointing to many California residents, it’s a slow-moving economic disaster for many fishermen, especially smaller vessels like those that dock around the Monterey Bay.

Fortunately, fishermen are used to adversity and challenge, so instead of giving up, they have been working together over the last several years to prevent whale entanglements and keep their fishery open. And their efforts are paying off.

In 2015, during a spike in reported entanglements on the West Coast, the California Department of Fish and Wildlife (CDFW) convened the California Dungeness Crab Fishing Gear Working Group. The group consists of fishery participants, scientists, conservationists, and state and federal agency representatives to address entanglements.

Known in the industry simply as the Working Group, it serves in an advisory capacity to the CDFW to, as its charter states, “provide the state of California with innovations, strategies, and management recommendations that support thriving whale and sea turtle populations along the West Coast, as well as a thriving and profitable Dungeness crab fishery.”

Fishermen involvement—especially with a group that might force them to change what they’re doing—might surprise some who saw fishermen taking much of the blame for entanglements from environmental groups and social media crusaders.

One of those environmental groups, the Center for Biological Diversity (CBD), was also invited to participate in the Working Group.

CBD established itself as a player in the crab fishery after it sued the CDFW for allowing endangered species to be harmed while under a regulated fishery permit (though that clearly wasn’t the intention), which helped inspire the preventative committee.

After a short time, the CBD abandoned participation because its reps were convinced the voluntary measures on which it was based wouldn’t work.

From there CBD co-sponsored the Whale Entanglement Prevention Act (AB 534), which aimed to mandate the conversion of California’s trap fisheries to ropeless gear by the end of 2025. CBD also petitioned the National Marine Fisheries Service after AB 534 was pulled when author Rob Bonta was appointed California’s attorney general.

Mike Conroy formerly represented the Pacific Coast Federation of Fishermen’s Associations on the Working Group.

“Far too often the news story is that there’s a whale entanglement, and not that there’s been a huge drop,” he says. “The drop in entanglements is the result of actions taken collectively by the industry.” While the blame laid on fishermen proves unfortunately—and unfairly—common, the reality is more complicated: When whale entanglements spiked in 2016 it came as a result of several factors.

Changes in water temperature have killed off primary food sources for humpback whales (krill), sending the whales closer to shore in pursuit of alternatives like anchovies—and closer to crab lines they hadn’t previously encountered.

Meanwhile domoic acid—a toxin found in some marine algae that blooms in warming seas and can then accumulate in shellfish—was being observed in crab viscera in levels exceeding the Federal action level of 30 parts per million. This forced CDFW to delay the season.

When the crab season finally opened in the Spring of 2016, it produced a shorter and more intensified interval for the fishermen to catch what they could. The heavy effort in the fishery, which normally took place in the late fall, or winter, coincided with whales moving closer toward the coast.

In the public arena, those environmental drivers were largely overlooked in favor of a more sensational—and misleading—angle. “It was, ‘These bad people are going out and harvesting whale, don’t have a side of whale with your crab,’” Conroy says.

Fortunately, the Working Group, which started in 2015, was already hard at work. It would go on to develop a Risk Assessment and Mitigation Program (RAMP) that has revolutionized practices and reduced entanglements even further. Those practices include the development of a network of fishermen on the water who have been trained to spot and appropriately respond to convey incidents to disentanglement experts.

Meanwhile, the CDFW conducts aerial surveys in advance of Working Group meetings so the committee has up-to-date information on humpback, blue whale and leatherback turtle activity. If the number of animals rises to a certain threshold, by rule it triggers action that ranges from fleet advisories to complete fishery closure.

RAMP has also advised CDFW and the Fish and Game Commission on 1) requirements for fishing gear alterations, 2) gear marking to ID whose buoys are where, and 3) completely new types of gear. “You can configure [currently] allowable gear in ways that minimize risk,” Conroy says. “In terms of alternative gear, it’s new equipment that hasn’t been used that has to be tested to show it’s functional for this application.”

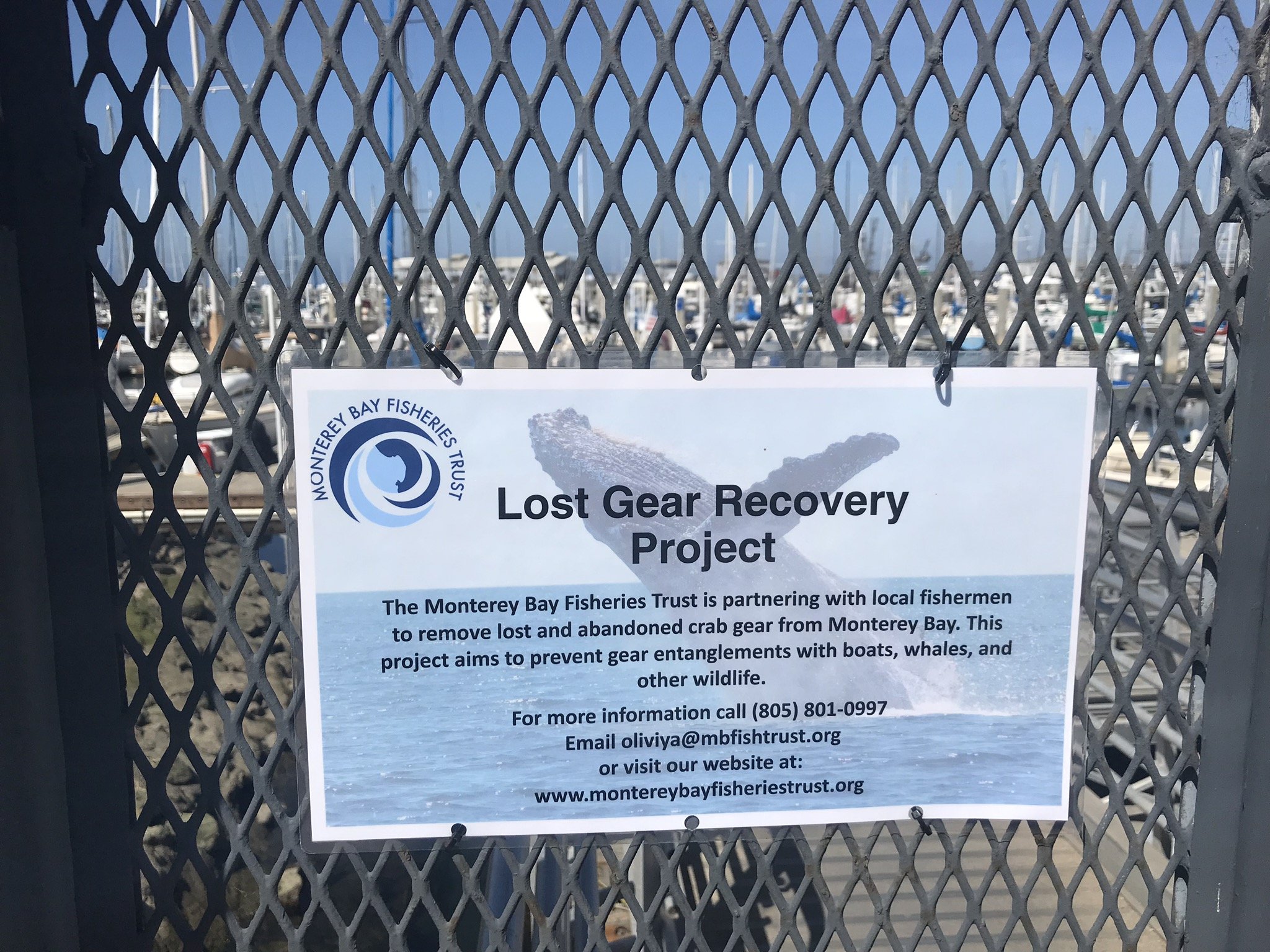

Meanwhile, while not directly attached to the Working Group or RAMP, another local fishermen-driven effort also helps limit entanglements, under the guidance of the California Department of Fish and Wildlife. Local fishermen collaborating on The Lost Gear Recovery Project, operating out of Santa Cruz, Moss Landing and Monterey, locates, identifies and removes stray equipment that could impact wildlife. They follow the model of ports state-wide.

The key outcome from all of it: Since 2020, there have been significantly fewer whale entanglements with commercial Dungeness gear along the California coast. That’s according to Ryan Bartley, a scientist with the Department of Fish and Wildlife.

“There’s a combination of factors at play—risk assessment, the cooperation of the fleet, best fishing practices and improved ocean conditions,” he says, “but in the commercial Dungeness crab fishery, we are trending way down.”

So the Working Group is doing exactly what it set out to do: reduce entanglements by working together to keep their fishery going.

“We might not agree with everything RAMP does,” Conroy says, “but in terms of risk of entanglement, looking at the last few years, it’s very good evidence that RAMP is working very well.”

Jenn Humberstone of The Nature Conservancy has collaborated closely with fishermen on the Dungeness Crab Working group and RAMP. She has a good handle on what’s been invested along the way. “It is important to recognize the restrictions on the fishing season, and the time fishermen voluntarily dedicate to the Working Group, lost gear recovery program and other conservation solutions require significant sacrifice of time and income,” she says. “Dungeness crab fishermen have demonstrated a strong commitment to stewardship and the long-term sustainability of this iconic fishery, which is critical to Central and Northern California coastal economies and coastal identities.”

For fisherman like Dick Ogg, who serves on the Working Group representing Bodega Bay, it only makes sense to caretake the source of his livelihood. “In reality we’re the true conservationists,” he says, pointing to dramatic upticks in humpback whale populations. “Our interests are to protect the environment and provide a sustainable resource.”

So the good news there is that the fishery—and the purchase of crab—has never been safer.

Meanwhile the delayed opening to Dungeness season means no local crab for Thanksgiving. But it’s fair to hope it arrives in time for Christmas.

More at California Department of Fish and Wildlife’s Whale Safe Fisheries website.